Who needs low-ABV cocktails when you have slow-ass bartenders?

This question, shared as a cheeky joke in an Instagram story, became a viral moment for Erick Castro, the legendary bartender behind San Diego’s Raised By Wolves and Gilly’s House of Cocktails, and host of the award-winning Bartender at Large podcast. In a follow-up story, he added: “This is not an isolated problem. … Many bars and restaurants are attempting to do ‘high volume’ without any of the training, systems, infrastructure etc. needed to accomplish said goal.”

Seeing Castro’s sentiments felt personally validating — the post-pandemic drinking landscape where I find myself waiting 15 minutes for a Martini and a Spritz has me feeling like the living embodiment of the Grandpa Simpson “Old Man Yells at Cloud” meme.

Back in my day we cared about ticket times!

But, clearly, it’s not just in my head, and in the modern era one can expect to wait longer for a drink at a bar. Certainly, it’s a privilege to come out the other side of the pandemic with my health and I’m thankful for every moment I get to spend enjoying food and drinks with friends and loved ones. But I would still like to maximize the time spent with a drink in hand rather than scanning the bar to see if my ticket got lost.

For bartenders, making drinks quickly and precisely isn’t just a parlor trick. Less time spent fumbling with bottles means more time engaging guests in conversation, noticing an empty glass and replacing it with another drink, running drinks to support a swamped server, or snagging an extra ticket from a weeded service bartender. Fast bartending is good service.

Good round building strategy and speed best practices carry over directly to the home bar, making you a better and more economical host. Round building and speed are for everyone. While I’d love to tell you myself exactly how to be quick, I’m four years removed from the last round of drinks I made behind a bar, so I’m rusty to say the least. So to learn how to make drinks quickly and efficiently again, I went to an active professional with some serious accolades.

Haley Traub is the general manager of Attaboy and the newly opened Good Guys in New York’s Lower East Side. She built her chops at Dutch Kills and Fresh Kills — bars that she described as providing “foundational training that was built to make me fast and accurate.” Those skills were put to the test in 2018 when Haley won the National Championship of Speed Rack, the country’s preeminent speed bartending competition. The most impressive part: In a competition built for contestants to free pour — a technique where the bartender utilizes the steady stream of a speed pourer to count out measurements quickly and mostly accurately — Haley took first place jiggering every single drink.

Now, she’s stepped out from behind the stick into a managerial role, training the next generation of speedy bartenders. I sat down with Haley to explore the nitty-gritty of order of operations, ideal dilution timing, and making a lot of delicious drinks quickly. She’s quick to point out that speed isn’t everything, reminding me that “it’s not just about physically making a drink fast. It’s also making sure that the best possible product is getting to the table.” That remains true for one drink or six drinks — every one of them needs to hit the table at the same time in the best possible condition.

Orders of Operations

Making a round of drinks competently involves the artful intermingling of two separate processes: the actual liquid-in-mixing-glass building of the drinks, and dilution, the process of adding ice and either shaking or stirring until the drink is sufficiently chilled and enough water has been added to bring everything into harmony.

Both of these processes have very specific orders of operations at Attaboy, based on choices the bar has made regarding ice and tools. They may not be tailor made for every bar setup — professional or home — but the fundamental thought processes are universal.

Liquid in Glass

Every round starts with setting up the tins, mixers, and rocks glasses that the drinks will be built in. The first ingredients added are miniscule — things like dashes or drops of bitters — or solid ingredients like mint leaves, berries, or sugar cubes. These have the added benefit of “marking” the vessel as a reminder of what drink is being built in it. The mixing glass with Angostura is for the Manhattan, the tin with the mint leaves is the Mojito, etc.

Once glasses are marked, it’s time to jigger. Attaboy uses stepped one-sided jiggers that look like tiny wide-mouthed measuring cups. These work well because the bar doesn’t use speed pourers.

The first jiggered ingredient category is citrus and other fruit juices. “Start as tart as possible, and work [your] way up to as sweet as possible,” Haley explains, meaning lime, then lemon, then grapefruit, then pineapple. This order ensures that the jigger needn’t be rinsed between individual drinks — the cocktail getting pineapple juice wouldn’t be contaminated by a touch of lime or lemon, but an unrinsed jigger’s worth of pineapple might be noticeable in a Gimlet.

After sour, it’s time for sweet. This time ingredients go from most neutral (simple syrup) to least neutral (ginger syrup), with agave and honey as in- between steps. A more flavorful syrup can follow simple with no fear of flavor bleed. The most neutral syrup can also serve as a reset for the juices that came before. In the context of a round, a drink with pineapple juice and simple syrup can get those ingredients back to back. The simple removes the trace pineapple, leaving the jigger ready to measure agave, honey, or ginger into another drink.

Syrups are followed by modifiers — liqueurs and the like — and finally spirits. Extra sticky and flavorful liqueurs like Maraschino generally require a jigger rinse, but there are contexts in which the spirit can do that work for you.

If you were making a Hemingway Daiquiri and a Rum Old Fashioned, for example, the light rum could rinse the Maraschino as it’s added to the Daiquiri, then you could go straight for a dark rum in the Old Fashioned. It’s all about understanding the context of every individual bottle pickup in relation to what’s come before and what’s up next.

The cardinal sin of fast bartending is touching any bottle more than once — if more than one drink in the round has lemon juice or simple or Angostura, every mixing vessel gets that ingredient the one time it’s in your hand. It may seem ridiculous, but it takes a couple seconds to rinse a jigger, and even longer to put a bottle down and pick it back up a second (or third) time. A busy bartender makes hundreds of cocktails a night and every one of these steps adds up.

Time for Ice

Knowing when to add ice and start diluting a cocktail requires just as much thought as the rest of the ingredients that went into it. Haley likes to describe it like cooking. “What needs to cook the longest? What’s going to need the most time? What is going to die quickest?” she says.

The Martini is a fantastic case study here. It’s going to take the longest to dilute in the mixing glass, especially if it’s just sitting built on the ice, but will die the fastest once the drink is transferred to a coupe, because it has no texture from shaking or ice to maintain temperature.

(I’ve worked places that say shaken cocktails should be poured last because the head will die as it’s walked to the table. Attaboy builds resilient heads on shaken cocktails by shaking on one massive rock. Those drinks are very impressively aerated.)

A Martini, or any stirred drink served up, can be iced first, left to cook while the rest of a round gets built, given a short stir once the rest of the round is complete, then poured and moved to the tray with the rest of the round to be walked to the guests.

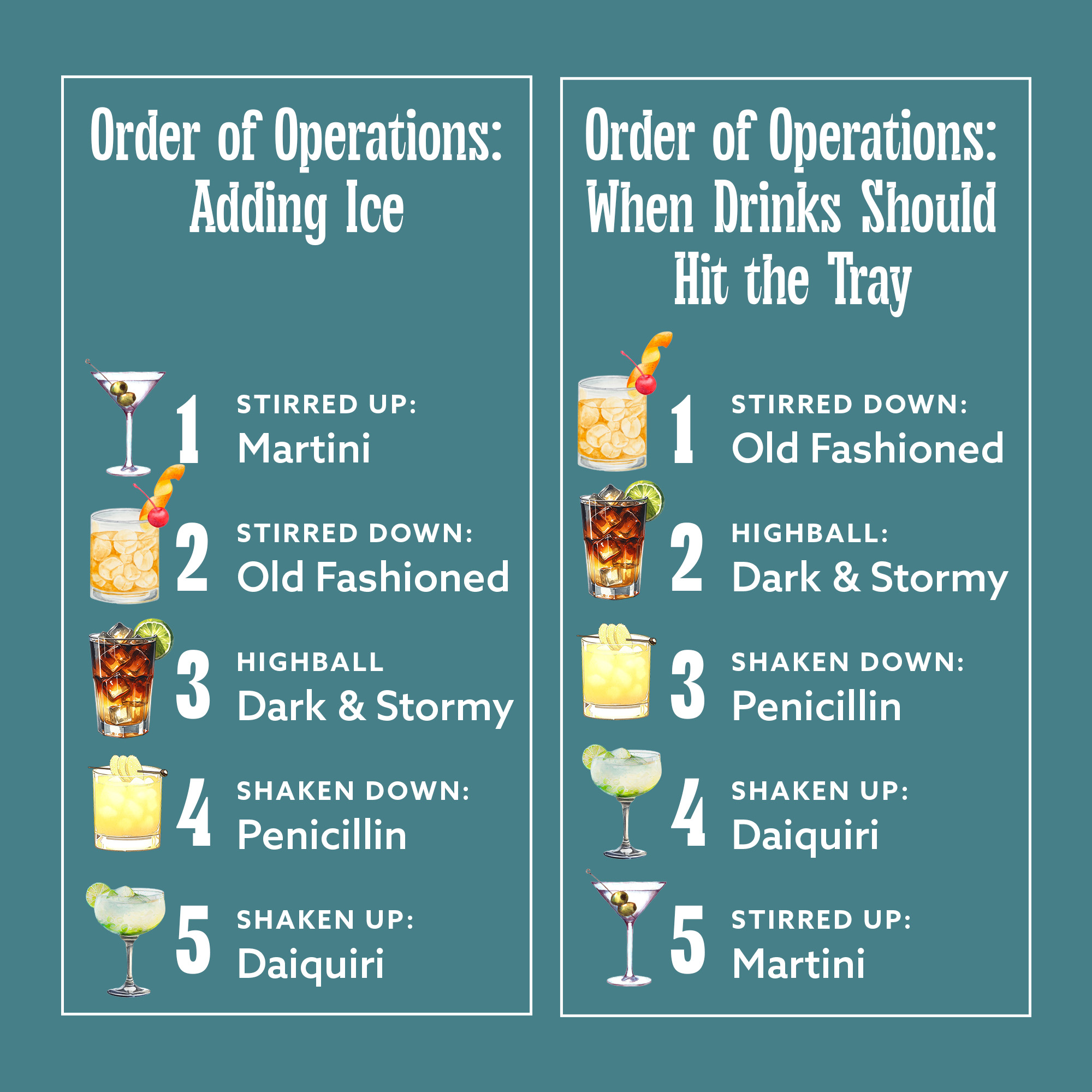

The order of operations for when to add ice is as follows:

- Stirred up (stirred drink served with no ice in a coupe)

- Stirred down (stirred drink served on the rocks)

- Highball (long drink topped with soda)

- Shaken down (shaken drink served on the rocks)

- Shaken up (shaken drink served in a coupe)

The order for when drinks should hit the tray is almost identical with one major change:

- Stirred down

- Highball

- Shaken down

- Shaken up

- Stirred up

This order works for Attaboy, in particular, because the only ice the bar uses is perfectly clear rectangular slabs of Clinebell-produced impurity free ice (yes, even for shaking). Big cubes dilute a cocktail substantially slower than wet, small pieces from a standard ice machine, or even Kold Draft ice. For Haley, it’s not about following this specific order of operations to a T, it’s about understanding dilution — how fast is the ice in your specific situation going to melt?

The icing order can also take into account individual ingredients. There could be a specific and important order in which you should shake two nearly identical cocktails based on a minor tweak. “Say we have a Daiquiri and a Brooklynite [a Daiquiri with honey instead of simple and added Angostura], both shaken up drinks, but we know the viscosity of the honey in the Brooklynite is going to keep that one alive a little bit longer,” she explains. Honey is a known foaming agent that sets a beautiful head on top of drinks, so that one should be shaken and poured first so both drinks arrive at a table looking fresh, instead of a stunning Brooklynite and a sad, flat Daiquiri.

It All Starts Before Service

Individual ability and fast hands can only help you to a point — the bar also needs to have systems in place that set bartenders up for success. At Attaboy, this means bar stations that are set up the same way every time, with every high-touch (common) ingredient mirrored at both bar stations. Low-touch items, like sherries, are kept in alphabetical order on ice between the two wells. “I don’t want anyone taking more than two to three steps to grab an ingredient,” Haley says.

That organization continues to the bottles in the well, with every spirit category grouped by type — whiskeys together, rums together, shaking and stirring gin next to one another (yes they have separate gins for shaking and stirring).

“Any given night we could be making 500 variations of cocktails,” Haley says, stressing the importance of this organization and consistency. “Ultimately, it’s just about making sure everything is accessible.”

Speeding Up

If only there were a magic bullet — some secret trick that would make every bartender blazing fast overnight. But as is true for most things, it just takes time and focused effort. “It’s literally hours of practicing jiggering, practicing dilution, running, mock tickets, and timing them,” Haley says.

To wit: Fill an empty bottle with water and practice measurements until the motion is second nature. Ask another bartender to time your rounds and if they’re interested — don’t be a jerk — offer to time their rounds as well. Try to get to the point that it feels effortless to make a six-drink ticket in less than 10 minutes, even when making conversation with guests or prioritizing building a quick cocktail for a solo guest at a bar.

I can guarantee you’ll find that, as ticket times trend downward, check averages will trend upward. Even if you don’t leave the bar with a few extra dollars in tips in your pocket, there’s a joy in knowing that you’re doing everything you can to be the best at the task in front of you.

This story is a part of VP Pro, our free platform and newsletter for drinks industry professionals, covering wine, beer, liquor, and beyond. Sign up for VP Pro now!